The rules change

The bike boom was waning by the late 70s. Racing frame builders were experimenting with novel materials and techniques. First it was aluminum tubes—glued, screwed, or welded. Then came molded carbon fiber frames. The new advancements were beyond van der Kaaij’s means. It was an echo of Wim Jr.’s lament a decade before: “the big machines…I cannot afford.” Publicly van der Kaaij was dismissive. Carbon? “That breaks in your hands.” Speaking of carbon in his workshop was akin to swearing in church.

Wim Bustraan Jr. died in May of 1983. As allowed by the original 1973 agreement, his heirs sold the RIH name to Cové. This eventually led to friction and a lawsuit with Cové. As a result, van der Kaaij was limited to 250 RIH-SPORT racing bicycles annually. While past production records suggest this was a generous allowance, it did not align with Wim’s ambitions. Also, he couldn’t put the name on anything but racing bikes.

Selling the RIHs to affluent amateurs and professional riders was easy. But it was a tiny specialized market. Van der Kaaij aspired to expand production, especially once Cové ceased making racing bikes. He sought another firm to make the replicas but the annual 250 bicycle limitation discouraged potential suitors. He later offered touring bikes made in the shop with the Vainqueur (Winner) brand name. It was not a unique name as bikes from Germany, Portugal, and Belgium had worn the same moniker over the years. The Swiss Weinmann firm introduced the popular Vainqueur center-pull brake in 1957.

Champions of the 90s: Women

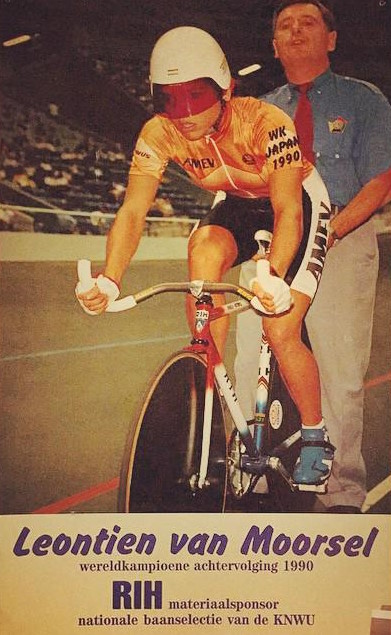

Wim was a sponsor for the Koninklijke Nederlandsche Wielren Unie (Royal Dutch Cycling Union) between 1989 and 1996. The partnership yielded seven world titles and a flurry of new RIH publicity. Leading the way were women cyclists Ingrid Haringa, Leontien van Moorsel, and Maria Jongeling.

“Ladies are still underpaid, and not just in sport,” Wim remarked, referring to van Moorsel, one of the most accomplished female cyclists in the world with four Olympic golds and nine world titles. RIHs also won silver and bronze medals at the 1992 and 1996 Olympics.

The cycling world kept changing. By 1994 UCI (Union Cycliste Internationale), the world governing body for sport cycling, finally discontinued old Joop’s motor-paced world title competitions. In effect, the sport had ended. Today, motor-paced racing still exists on a small scale in Europe but remains mostly in the form of keirin. In both instances 98 cc Dernys with top speeds of 65 kph (40 mph) are the pacers. Keirin became an official Olympic event in 2000.

The industry shifted away from skilled artisans hand-building steel frames towards mass-produced carbon fiber frames, with much of the fabrication relocating to Asia. Demand for high-quality, custom-fit European metal frames melted.

The end

Reflecting his age and market demand, by 2003 Wim had throttled back his daily time in the workshop to six hours. Wim resumed building frames at the firm’s historic rate of two per week. “It takes time to do it right; we still make these bikes by hand and I’m not getting any younger.”

There was a time when almost every serious Dutch cyclist wanted a RIH. On June 1, 2012, RIH-SPORT closed. On a damp Sunday two weeks earlier, nearly 100 cyclists gathered at the shop to honor Wim. Past champions and hipsters on fixies pedaled their RIHs together on a tribute ride through the streets of the Jordaan. The day ended with an emotional Wim trying to shake each person’s hand.

Seventy-five year old Wim van der Kaaij had been part of the shop since 1948 and owned it for the last 39 years. He worked hard to find a successor. His son, who had painted frames in the shop, declined. Holding true to steel, RIH lost the battle to time and Asian manufacturers. One of the last of the great Amsterdam frame builders had put down his tools, no longer at the bench.

All things had changed. Even the working class Jordaan had gentrified. Wim said he could no longer afford rent on the Westerstraat. Besides losing ownership of its name it seems RIH never even owned the Westerstraat workshop.