Olympics drama

Building bicycles for winning racers brought significant advantages. Cyclists Arie van Vliet and Jan Derksen raced RIH bicycles to victory, claiming three world championships in 1936, 1938, and 1939. Van Vliet also secured Olympic gold in the 1,000 meters time trials at the 1936 Olympics.

Van Vliet nearly achieved another gold medal in the individual sprint, but was edged out due to a controversial finish involving German competitor Toni Merkens. Despite being fined 100 Reichsmarks (a not insignificant $40 USD at the time) for interference, Merkens retained the gold medal, possibly influenced by the event’s backdrop—a 1936 Berlin Olympics promoting a resurgent Germany. This led to the Dutch press dubbing it “The Disgrace of Berlin.”

Politics aside, win and lose, RIH’s name was in the news. Interestingly, van Vliet and Merkens went on to become friends for decades.

Miserable occupation

The Netherlands faced tremendous hardships during the war years. Occupied by the Germans in May 1940, the situation darkened as rationing was soon introduced. Major bicycle factories were demolished or had their machinery transported to Germany. Occupying forces frequently confiscated (stole) bicycles, often clearing out bike storage stalls at train stations. With bicycle spare parts scarce, riders had to resort to improvised repairs. By the war’s end, the Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (Central Agency for Statistics) reported that half of the 4 million bicycles owned before the war had been seized. The remaining bicycles were often barely operational, with riders navigating on tireless rims. Rubber imports from the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia) were cut off, and any available rubber was redirected to support the German war effort.

RIH survived by focusing on repair work and crafting a few race frames. In an attempt to preserve a sense of normalcy amid the persecution and violence, the occupiers permitted some bicycle racing events. Motor-paced racing was allowed, and Joop continued to compete in these races.

The Germans obligated Dutch workmen to forced labor service beginning in 1942. Nearly half a million Dutch individuals were sent to work in German factories. Records suggest that 28-year-old Wim Jr. was among those slated to work in a Telefunken factory in Germany.

Suspicious behavior?

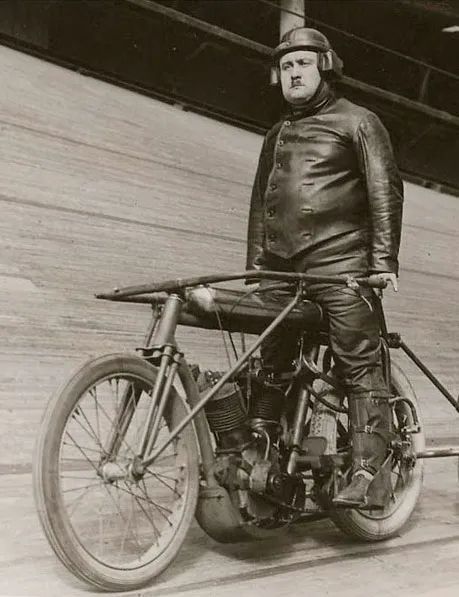

By late July 1942 all men’s bicycles in Amsterdam had to be turned over to the occupiers (“Ik wil mijn fiets terug!”). But on 23 September 1942, somebody reported Joop for suspicious behavior. He had been spotted riding a “gentleman’s bicycle—Gazelle” while sporting “a leather motorcycle suit, leather pants.” Fortunately for Joop the police report concluded “no suspicion.” Joop talked his way out of a tight spot, explaining he was simply on his way to his motor pacing job wearing his work clothes.

Post war winning

Emerging from war the most popular Dutch sports were football and cycling. Between 1946 and 1948 renowned cyclists Gerrit Schulte and Ge (Gerard) Peters joined van Vliet and Derksen in winning four more championships on RIHs. Fortunately, not only the business but its reputation survived the war.

As the 1950s dawned the Dutch racing community was composed largely of family-run small frame building shops. Those men and their sons were celebrated for their fine designs, deep experience, and masterful craftsmanship, making their bikes consistently victorious. Strong personal bonds formed between racers and these skilled artisans.

Despite automobile usage gradually supplanting bicycles, track racing was at its pinnacle of popularity in Amsterdam. Dutch cyclists Jan Pronk, Piet van Heusden, Arie van Vliet, Frans Mahn, Jan Derksen, and Arie van Houwelingen dominated the sport, clinching six world championships on RIHs. The demand for road and track bikes surged.

Craft takes time

But the hard truth was that RIH remained a couple of guys in a cramped workshop with a bike on display in the window and a handful of tires lining the shelves. The RIH purchasing process was unchanged. You traveled to the Westerstraat in the busy Jordaan. You were confronted with a sparsely stocked showroom with a nearly bare floor. On the wall hung a few cyclist’s laurel-draped portraits. Then came a personal interview and measurement by the typically straightforward Bustraan.

Finally! Your order was…on the waiting list. Waiting lists became the norm for years (the Limburgsch Dagblad claimed that wait times were as long as eight months even in 1974). Records show that in the late 1950s Wim Jr. and Wim never produced more than 77 bicycles annually. RIH was a small operation crafting jewels.

For RIH the fifties meant growing acclaim, a booming post-war economy, and high demand for its product. But it also faced a growing waiting list and a tiny workshop. Why were the Bustraans slow to adapt to these challenges? Maybe it was the personal upheaval of Willem’s mid-decade death. Perhaps it was limited access to capital for expansion. Neither Bustraan nor the young van der Kaaij had experience in designing or managing a production line. Wim Jr. said it plainly, “I could not do it all on my own.”

And there has been talk of Bustraan familial stubbornness and self-reliance. De Tijd aptly noted,“if the Bustraan family’s character wasn’t so deeply rooted in independence, there might already be a large factory standing at the edge of town by now.” Speaking as a Bustraan, the author finds this entirely plausible.

The one clear marketable asset was the name RIH.